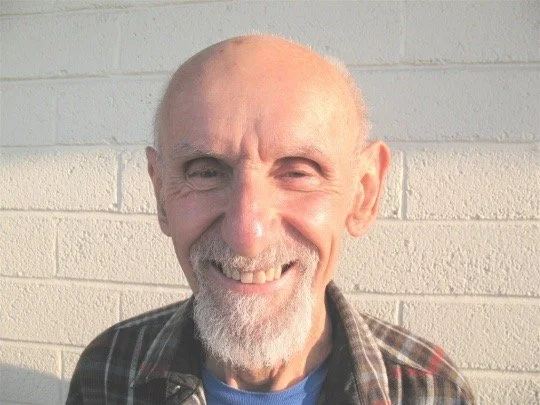

Nonviolence in Action: Remembering Louie Vitale

Louie Vitale leading a procession protesting war at the US Capitol in 2006.

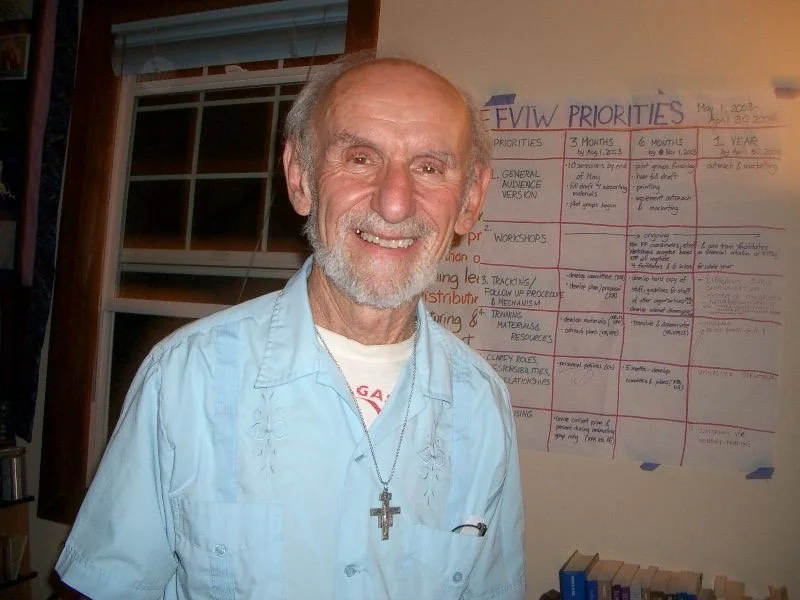

In 2012, Louie Vitale received an honorary doctorate from the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. The building was packed with students and their families. The highlight of the event was the conferral of three honorary doctorates. Two scholarly gentlemen collected their award and delivered magisterial exhortations brimming with scholarly exegesis. Then it was Louie’s turn. His presentation was short and to the point.

“I’ve discovered in my life,” he said, “that love is what matters in the end. And all I can say is: I love you! I love you! I love you! I love you!” And then, with a final, rousing “I love you!” as he waved his arms in a vigorous gesture of blessing, he sat down.

Louie receiving an honorary doctorate at Catholic Theological Union.

The crowd broke out in long and delighted applause.

Friar Louie Vitale, OFM—a Franciscan priest, past provincial of the St. Barbara Province of the Franciscan order, co-founder of the Nevada Desert Experience, which worked with other organizations to successfully end U.S. nuclear weapons testing, founder of the Gubbio Project, which opened his church in San Francisco to the unhoused, co-founder of Pace e Bene Nonviolence Service, and an enduring exemplum of the nonviolent life—died in Oakland, Calif. on Wednesday, September 6. He was 91.

Louie’s longtime colleague and friend, Anne Symens-Bucher, accompanied him in those final days at the Mercy Center, his home for the past five years. Sitting at his bedside she stitched together Louie’s far-flung friends by text and invited us to join her in saying the rosary as Louie lay nearby. It was a great gift to be able, by Face-Time, to quietly share our love for this great apostle of love. Like the graduation audience in Chicago, we had all experienced his rousing “I love you” in words and deeds for many decade.

Via Face-Time, I shared my love for him from Chicago, and also my conviction that, in his coming new life, he would be met exuberantly by Saint Francis of Assisi.

But for the rest of us, we did not have to wait. We met Saint Francis in the life of Louie Vitale.

He embodied in our time so many of the 13th century saint’s facets of holiness: an abiding hunger for peace, justice for the poor and excluded, love of nature, and the longing to draw close to the presence of God, including through a contemplative life lived in the midst of the chaos of society.

Louie was a nonviolent change-maker actively immersed in one peace movement after another, challenging his government’s wars in Vietnam, Central America, Iraq, Afghanistan and many other parts of the world. He spent long stints in prison for nonviolent resistance to torture and war-making. For thirteen years he was the pastor of St. Boniface Catholic Church in a low-income neighborhood in San Francisco, where he was actively involved with Religious Witness with Homeless People, an interfaith campaign challenging poverty and government policies of harassment against poor and homeless people. All of this and much more found its way into a graduate course entitled “Liberating Nonviolence” we team-taught a dozen times at the Franciscan School of Theology, mentoring the next generation of peacemakers.

Louie’s family

The Journey

Louie grew up in Pasadena, California. After attending military school he joined the United States Air Force in 1958, where, as a captain, he became a pilot and navigator on nuclear-capable jets. His father, Louis Vitale, Sr., had long expected his only son to follow him into the management of a highly successful seafood company that he had started in Los Angeles after arriving as an immigrant from Sicily as a young man. He was stunned and perplexed when his son announced, after finishing his tour of duty with the military, that he had decided to become a Franciscan.

Louie Vitale was enthralled with the life and work of Francis of Assisi. The son of a wealthy merchant, Francis grew up steeped in the vision of chivalric honor and romantic love. He went off to combat in a war between Assisi and a neighboring city-state. During one of the battles he was captured and spent a year as a prisoner of war. After being ransomed by his father, he underwent a profound conversion experience. In 1208 Francis took radically to heart the thoroughgoing demand of Matthew 19:21—Jesus' call to the rich young man to give everything away and follow him. Francis, burning with the desire to imitate the poor and crucified Jesus, renounced his claims to his family's wealth and espoused "Lady Poverty" or "Holy Poverty" as his lifelong companion.

Like Francis centuries before, Louie had observed the implements and dynamics of war at close range. Vitale did not serve in a hot war – his stint in the air force took place between the Korean and Vietnam conflicts – but he was actively enlisted in the Cold War struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union. Although he felt the allure of Air Force fighter jets, Vitale nevertheless began to question the projection of U.S. power they represented. He also worried about the threat they posed. Once as he and his crew were flying a routine mission along the U.S.-Canadian border, they received orders to shoot down an approaching aircraft determined by headquarters to be a Russian military jet crossing into U.S. airspace. Vitale radioed his base three times for confirmation, and each time the order was reiterated. Finally, the crew decided to make a visual inspection. When they did, they saw an elderly, smiling woman waving to them. At the last moment they averted shooting down a commercial airliner. This incident contributed to growing qualms about remaining in the military. In contrast to the life of a jet pilot, he felt increasingly drawn to religious life.

The roiling social conflict of the 1960s – and the nonviolent social movements that were active then – became a kind of formation process for Louie. In the 1960s and 1970s, he had worked actively on a number of social justice and peace fronts in addition to his anti-war and farm worker ministries, including solidarity work with welfare recipients and helping to found the U.S. Catholic Conference’s Campaign for Human Development.

Louie founded and served on the staff of the Las Vegas Franciscan Center in 1970 after completing a doctorate in sociology at the University of California at Los Angeles. He became the pastor of St. James Catholic Church, a parish in a low-income neighborhood on the west side of Las Vegas.

Louie had been elected vice-provincial at the end of the 1970s by members of his province— a jurisdiction that embraces much of the western United States—and was abruptly elevated to superior of the province when Provincial Minister Fr. John Vaughn, OFM was called without warning to Rome to lead the worldwide community of Franciscan men as the Minister-General of the Friars Minor of St. Francis of Assisi.

Through his active participation in the United Farm Workers’ struggle for the rights of the migrant poor and his visible opposition to the Vietnam War, Vitale was regarded as an emphatic advocate for justice and peace. In the wake of the heady days of the Second Vatican Council, Vitale was seized by the conviction that the work for peace and justice was central to the identity of Christians. This in itself was not unique. In the wake of Vatican II a growing number of Catholic clergy, women religious, and laity drew a similar conclusion and began to transform an insular church that had often supported social structures that reinforced injustice and war into a community prophetically seeking change.

What set Vitale and a relative handful of others apart were not their theological conversion but how they put it into practice. In his case, he marched and fasted with Cesar Chavez, vocally and dramatically decried the U.S. war in Vietnam, and publicly counseled and stood with young men who burned their draft cards and defied conscription into the U.S. armed forces. He supported the nonviolent civil disobedience of Daniel and Phillip Berrigan and lent his support to a wide variety of other nonviolent social struggles. Fr. Vitale’s years in Las Vegas motivated him to work with others to launch the Nevada Desert Experience, a faith-based movement to end nuclear testing at the nearby Nevada Test Site and to co-found Pace e Bene.

Perhaps my favorite writing of Louie’s was the series of prison letters he sent us when, in his 70s, he began to undertake a series of longer jail stints, usually about six months each, protesting torture.

At the end of a letter sent during a 2008 jail sentence, he wrote:

The cell door clangs shut. Now I am alone. But instead of trying to escape this solitude, I enter it deeply: This is where I am. Here in this empty cell I have begun to experience prison in the way James W. Douglass in Resistance and Contemplation describes it: not as “an interlude in a white middle class existence, but as a stage of the way redefining the nature of my life.” I have sensed this transformation, little by little. These days are a journey into a new freedom and a slow transformation of being and identity: an invitation to enter one’s truest self, and to follow the road of prayer and nonviolent witness wherever it will lead.

I am in this little hermitage in the presence of God, in the presence of the Christ who gave his life for the healing and well-being of all. I am also in the presence of the vast cloud of witnesses, some of whom are represented in the icons that have multiplied in this cell, gifts sent to me from people everywhere: Oscar Romero, Martin Luther King, Jr., Dorothy Day, Steven Biko, the martyrs of El Salvador, John XXIII. All those who have given their lives to fashion a more human world. At the same time I experience a deep connection with my fellow prisoners and with those outside these prison walls, including those who have sent me many letters and expressions of prayer and support.

In my little, empty cell, I experience a growing awareness of the communion of saints -- and of the possibility of a world where the vast chasm of violence and injustice enforced by torture and war is bridged and transformed.

Simply powerful. And true.

Through all of this Louie brought a down-to-earth humanity. We talk about nonviolence being “love in action.” If this is the case, Louie was my great nonviolence teacher. For him, it was not just at a graduation ceremony where he declared, “I love you.” It was virtually every moment of every day.

And all with grace. And joy.

He could be anxious. He once told me his parents thought he was an anxious kid, and he never entirely shook it. But there was also a kind of ease with which he did his biggest things—heading off to jail for six months, traveling to Iran on a people-to-people peace mission, heading up one social justice campaign, and then another, and then another—because he knew who he was and what he was here to do.

It was a great gift to learn something about all of this from Louie.

* * *

In 2003 I published Pilgrinage Through a Burning World, a book that recounted the Nevada Desert Experience’s campaign to end nuclear weapons testing. A lot of this book is about Louie, even though he was not particularly good at organizing. There were many other great organizers involved, including Anne Symens-Bucher. Louie, instead, was more the movement’s catalyst and, ultimately, its soul.

The antinuclear testing campaign was just one of many, many efforts Louie was part of for justice, peace, and well-being for all. Many other vignettes could be posted from many different angles of Louie’s life. But below are some that shed some light on the inimitable Louie Vitale.

Thank you, Louie, for everything.

Ken

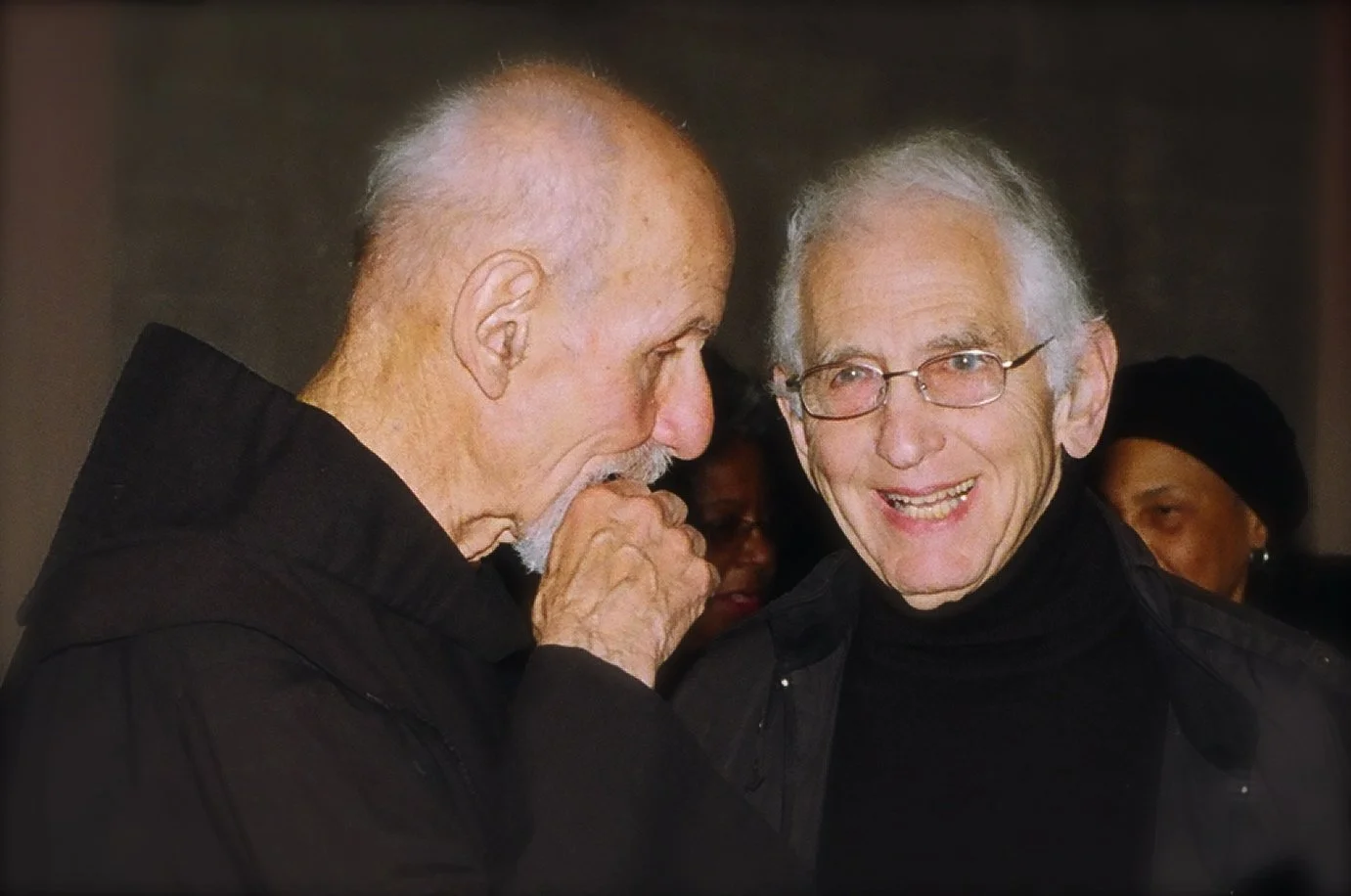

Louie Vitale and Daniel Ellsberg conferring during Louie’s 79th birthday party in San Francisco’s North Beach district.

Excerpts from: Pilgrimage Through a Burning World: Spiritual Practice and Nonviolent Protest at the Nevada Test Site (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2003):

In 1981 Louis Vitale received a letter from the Minister-General in Rome calling on Franciscans throughout the world to sponsor creative projects to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the birth of St. Francis in 1982. Vitale – a friar who had a long history of peace and justice activism and at the time was the provincial of the Franciscan Friars’ St. Barbara province, a jurisdiction that included much of the western United States -- thought that a project highlighting Franciscan peacemaking would be appropriate, especially at a moment when the newly-elected Reagan administration was vowing to modernize the U.S. military, including the three legs of its nuclear weapons system: sea-based submarines and ships, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, and its fleet of jet bombers. Not only did this renewed build-up seem to Vitale, a former U.S. air force pilot, likely to increase the danger of nuclear war, it would also lavish economic resources on weapons systems at a time when social programs would be slashed across the U.S.

Louie at the Nevada Test Site.

At the time that he was mulling various possibilities, Vitale was approached by a recent graduate of the Franciscan School of Theology in Berkeley about the possibility of working for the St. Barbara province on peace issues. A former professor in Health Education at the State University of New York at Cortland who had decided to study theology in California, Michael Affleck had been actively organizing peace-related events in the San Francisco Bay Area since Daniel Berrigan had taught a course on nonviolence during the 1980-81 academic year at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. Vitale was delighted with Affleck’s proposal and discussed his organizing a series of peace-oriented events for the province to mark St. Francis’ birthday the following year.

I said I would support this,” Vitale later recalled, “but only if one of the events took place at the Nevada Test Site.” Vitale, who had lived and ministered in Las Vegas for many years, had long been concerned about the U.S. government’s testing program at the test site. This was brought into sharp focus by a conversation that he had once had in the early 1970s with the editor of Commonweal, a progressive Catholic weekly magazine. At the time the activist community was still largely focused on ending the U.S war in Vietnam, but something the editor said caught Vitale’s attention. Even if they stopped the bloodshed in Indochina, Vitale remembers Jordan saying at the time, there are still tens of thousands of nuclear weapons aimed at the world’s children. This comment proved pivotal for this Franciscan priest who was motivated by his faith to work for a better world and who, at one time, had played a part in the nation’s strategic nuclear force structure. He had become curious about what the government was doing at the Nevada Test Site and was told by a friend with contacts within the U.S. Department of Energy that the test site had situation in a remote location, in part, to discourage protest. Vitale took this as a personal challenge.

Louie in the Nevada desert.

Affleck visited the test site. He later said, “I kept that trip very much in my heart and I began to think, Maybe we could have a vigil out there. Maybe this is what needs to happen. Maybe our response to the year of St. Francis would be to have a time in the desert where we are witnessing about this evil but we are going out in the real desert experience, not knowing what questions to ask, not knowing what direction we’re going to take, waiting, really, for the word of God to come to us, to give us some understanding of what has to happen next…. The whole thing began with the idea that we could pray and wait for some guidance on what to do, and that maybe out of this experience, out of the collective group understanding of those of us who went out there every day, we’d figure out what to do. But we didn’t know when we started…”

To conclude the 40 day vigil, 19 people—including Vitale, Bucher, Dan Ellsberg and others—were arrested as they crossed into the test site. “After being handcuffed, the nineteen were bussed sixty miles north to Beatty where they were jailed briefly and then presented before Nye County Justice Court Judge William Sullivan. The arrestees refused to pay the required $100 bail he imposed. The group desired to continue its vigil in jail through Easter. As Affleck recalls, “The judge ordered the protesters released but Louie Vitale, OFM…suggested that they would not leave. The judge said that if they did not leave they would be held in contempt of court and physically removed from jail. The judge voiced sympathy for ending nuclear testing.”

Louie Up Close

NDE participant Jane Hughes Gignoux reflected on her experience in an essay entitled “A Journey to Nevada,” quoted in Pilgrimage Through a Burning World:

Two white converted school buses pulled up in front of the community center in the tiny desert town of Beatty, Nevada. We were led, handcuffed, into a large, empty room and told to wait. It was then I saw Louie, still wearing his brown Franciscan habit. He came in through the door smiling easily and almost at once spotted a young man he apparently knew. Without hesitation he walked over to the young man and, in one huge sweeping gesture, lifted his arms, bound at the wrist, up and over the fellow’s head and then down, holding him in a warm embrace. It was such an easy, natural gesture, accompanied by words of welcome and comfort. “Wow!” I thought to myself, “That’s how I want to be – light-hearted, loving, compassionate.” It was true, of course, that Louie had been arrested many times over the years. Nevertheless, as I contrasted his performance with mine, I was aware of how much I had to learn about letting go and surrendering. When I saw how Louie radiated faith, hope, love from the center of his being, I resolved to keep at it until I could do the same.

Presently one of the marshals came and cut away our plastic handcuffs. Then I saw Louie in a corner of the room remove his brown robe, fold it reverently and, with this gesture, return to his chosen disguise as an ordinary man. In his plain black tee-shirt, cotton trousers, and sandals he could have been a truck driver, a salesman, a farmer, anyone at all. In fact, Louie Vitale is no ordinary man. He is the head of the Western Province of the Franciscan Friars with extensive responsibilities, and very much the spirit behind the protest and vigil movement at the Nevada Test Site. Except for brief moments, he prefers to remain in the background, allow others to coordinate the many complicated preparations that go into these protests. How exhilarating to be in the presence of a person who had no need to prove his power by attempting to control others. Here was someone who understood the source of his power and who obviously knew that no one could rob him of it. That, combined with his utter honesty and compassion, marked Louie as an example of a true leader. If such people were in government and business, how different a world it would be.

“Go with the Mystery”

NDE participant Patricia Roberts, reflected tenderly on her time in the desert in March, 1988 and the ineffable and inexplicable power of its continuing presence in her life:

Our group prepared here in New Jersey for the event yet there is no doubt that crossing the line was rather scary. The spiritual high point – and I’ll never forget it – was when a long and intimidating line of guards came towards us, demanded that we kneel and handcuffed us. I’d never been to the desert and to kneel there in its vastness, among blooming desert places – as one by one we sang peace songs – is a moment in my life for which words are not adequate. A feeling that all will be well. A freedom.

In December 1988 – nine months after I’d been to the desert – my husband of 33 years died, quite unexpectedly. For some strange reason, as devastating as this was, I feel that what I’d been part of at the desert softened his death. I wrote about this to Father Vitale; he replied saying, “Go with the mystery.” I am tearful thinking about this, but it is powerful and comforting to contemplate.”

Now, with Louie’s death, we hear his powerful words again: “Go with the mystery.”

Toby Blomé has sent out a list of “inspiring videos” with Louie speaking, or, in this case, about him:

What is Louis Vitale? Explain Louis Vitale, Define Louis Vitale, Meaning of Louis Vitale

Father Louis Vitale: Love Your Enemies - . Very inspiring talk that Includes overview of Peace Delegation to Iran in 2009, and many photos with Martha Hubert's beautiful “Peace with Iran” banner. (58 min.)

Interfaith Service in Solidarity with Homeless People - Downtown Berkeley - 09 April 2015

Father Louis Vitale on Prop L: Unjust, Unwise...and downright silly. - 2010

Father Louis Vitale speaking at Occupy SF - 2011 (7 min.)

Interview with Father Louis Vitale - 2007. Truthout's Executive Director Marc Ash interviews Father Vitale after his arrest at Fort Huachuca in Arizona protesting the training of interrogators in torture. (8.23 min.)

Dolores Huerta and Fr. Louis Vitale, In Conversation. https://youtu.be/0xMLW2Ob4Ts?si=JzB4WcX5Iza-TyW9.

Thank you, Toby!