Thomas Merton, Fifty Years On

Is it already five decades since Thomas Merton left us?

Today we celebrate International Human Rights Day around the world. In the US, for example, the American Friends Service Committee is marching at the border in support of the Central American migrant caravan and the Sunrise movement has organized mass protest at the US Capitol demanding Congressional backing for a Green New Deal. (Pace e Bene board member Rev. Lennox Yearwood, Jr. helped prepare the 1,000 young people for this event at a training on Sunday.)

At the same time, some of us are also marking Merton’s death 50 years ago today. While it’s impossible to know what Merton would make of these particular nonviolent initiatives, I suspect he would have found them important steps toward a saner world. Who knows? He might have even joined in.

Thomas Merton – a monk, writer, and poet – was also what we might call a spiritual director of the faith-based peace and justice movement for the last years of his life. He hosted a pivotal peace retreat in 1964 at his monastery, Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky; wrote books and articles on nonviolence, racial justice and nuclear disarmament; and mentored many organizers. An activist in the Civil Rights movement once told me that he drove several times from Nashville to Gethsemani for strategy sessions with the monk. Merton would play hooky from the monastery and the two of them would drive around for hours reflecting deeply on the movement and its direction.

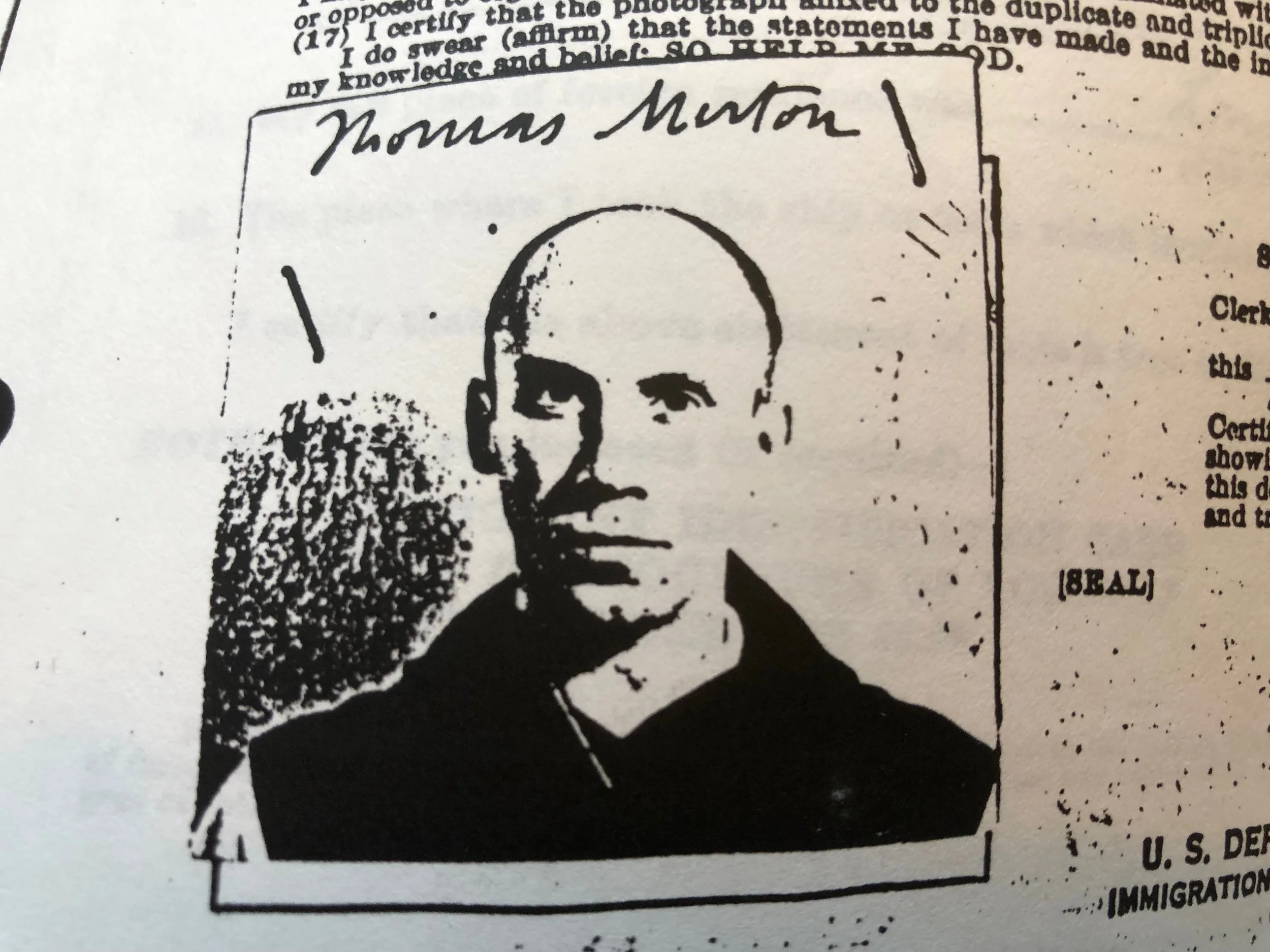

Thinking about today’s milestone – half a century since Merton’s sudden death in Bangkok, in the midst of a powerful pilgrimage across Asia – I fished out the dossier of redacted files that the FBI had kept on him, which has since been declassified. Likely incomplete, it mostly is comprised of immigration paperwork. (Merton had been born in France and had immigrated to the US in the early 1930s.) But there were also a few documents of a political nature, including Merton’s support for a draft resister, Joseph Mulloy.

In February 1968 Mulloy marched with a group of supporters to the local draft board in Louisville, where he delivered a letter from Merton.

The letter—which the FBI copied and shared with other branches of government (“Secret Service advised locally concerning 2/23/68 demonstration. Military Intelligence cognizant”)—communicated Merton’s strong support for Mulloy. In this missive he wrote: “As spiritual advisor, I have been consulted by Joseph Mulloy who is seeking to follow his conscience in opposition to war. I believe he has every right to do so & also believe that his rights are being denied him. Consequently, doing my simple duty as a priest, I have given him encouragement & support in his fight for his right.”

In 1978 I was at Gethsemani for the festivities held on the tenth anniversary of Merton’s death. A young graduate student studying theology at the time, I was moved deeply by his writings and wanted to draw closer to his vision. Although I didn’t know it at the time, I was on the threshold of a new direction in my life at that very moment, an unexpected path of nonviolent activism for justice. Reading Merton’s numerous books, and letting his vision of things work on me, was slowly preparing me for this.

He became, in effect, my spiritual advisor.

I am grateful for Merton doing his simple duty—not only for Mulloy but for the countless others, including myself, who over the past half-century have benefitted from his clear-sighted call to the spiritual journey of nonviolence and justice. Thank you, Thomas, for the encouragement and support you showered on so many of us.

The images of Thomas Merton in this blog are from the FBI dossier – from 1940, 1948, and 1968.